This article was originally published at: http://www.theislamicmonthly.com/celebrity-scholars/

Today, a new set of Muslim scholars have emerged—on the red carpet. They are decorated in traditional pious garb: long flowing gowns and trendsetting scarves. They stride elegantly down the crimson walkway where they are met by follower-fans who eagerly praise and lionize them. In this Hollywood reality, celebrity scholars are exalted for their religious knowledge.

In his account of America’s first Muslim college Scott Korb observes that “celebrity follows knowledge in American Islam.” Korb is surprised by Muslim students’ fervent veneration of their religious teachers. In Islam sacred knowledge demands reverence, a concept best reflected in one’s adab or respectful comportment towards his or her teacher. Here, however, Korb hits on the more peculiar phenomenon of Muslim celebrity culture.

This culture is most prevalent in the social media realm where Muslim scholars maintain carefully crafted public profiles on sites like Facebook and Twitter. These scholars diligently offer 140-character smidgens of religious wisdom. They also post personal anecdotes, self-help advice, and the occasional political grievance. Sometimes, they even share scholarly “selfies,” oblivious to the narcissism inherent in such a practice. Although many of their posts are vague, if not shallow in nature, thousands of followers evince gushing admiration through “likes,” “favorites,” and “retweets.” The lionization of scholars for their down-to-earth religious swag is reminiscent of the devotion of millions of followers to popular personalities like Oprah or the Kardashians. The game is the same. The names are different.

A troubling symptom of this increasing online phenomenon is the perpetuation of an identity politics. “My shaykh is better than your shaykh” is the motto in contemporary American Islam. Many celebrity scholars hail from different popular Islamic institutions like AlMaghrib, Bayyinah, Zaytuna, and SeekersGuidance. Posting in tandem with their institutions, these scholars act as plugs for their specific brand of Islam. Muslims, in turn, identify themselves with one or more of these institutions. They adopt their ideologies and characteristics. A wholly modern form of identity is fashioned characterized by one’s dogmatic attachment to his or her own Muslim camp. Critical thinking and engagement fall out the window as each Muslim camp claims monopoly over the “true” meaning of Islam. We would do well to heed the warning of Shabbir Akhtar, who wisely states that dogmatism in any camp is the common enemy.

In my use of dogmatism, I am not referring to the notion of submitting to authority and the precedent of the past. There is a significant place for this in our tradition. Rather, I am speaking of a “servile conformism,” a specific form of dogmatism that even al-Ghazali criticized during his time, which is anti-intellectual and overtly ideological rather than truth-seeking.

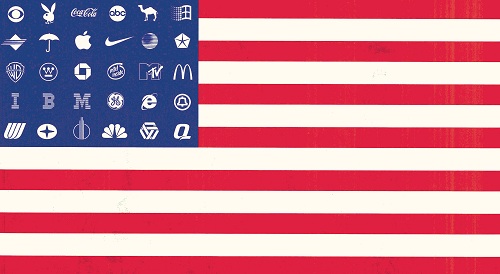

Perhaps one of the biggest threats celebrity scholar culture poses to the Muslim community is a dramatic rise in anti-intellectualism. Scholars peddling a feel-good Islam post short cookie-cutter comments on religious matters (see Fig. 1). Instead of reading a book, followers can learn all they need to know about Islam by merely scrolling through a string of instructive “tweets.” In reality, no actual learning takes place. The unique engagement one has with a book invites one into a unique dialogue with the author. It inspires critical thinking skills and sustained learning. This is radically different from reading a brief “tweet” or Facebook post, which are more often than not, simplistic fleeting thoughts. These Islamic sound bites in no way sufficiently explain complex religious issues that scholars of the past discussed over the course of centuries.

Even more unsettling is the fact that social media induces a strange form of complacency within Muslim religiosity. A scholar may request a du’a for a specific occasion, but rather than immediately dropping technology to make supplication, Muslims hasten to “like,” or “favorite” the post. By acknowledging a scholar’s pious comment, Muslims feel they have completed their religious duty for the day (though they’ve failed to make the journey from the computer screen to the prayer mat).

This same culture of complacency characterizes celebrity scholars’ social and political posts. To take a more recent example, the Boko Haram scandal produced no shortage of scholars joining the hashtag #BringBackOurGirls campaign. Though they were certainly well-intentioned, their posts were ineffective insofar as they merely accumulated a few hundred “likes” and did not in any way galvanize practical action. It seems that Muslim scholars simply wanted to show the world that they too were aware of an issue that everyone else was talking about. In condemning the Boko Haram, they felt they’d made a difference. This is emblematic of a larger online phenomenon wherein everyone shows solidarity for one single issue (one they were probably ignorant of before) and subsequently feels satiated by their noble social activism. Celebrity scholars and follower-fans must challenge the superficial satisfaction gained by the click of a button in both religious and sociopolitical matters. Instead, scholars can use international events to comment on related taboo issues in their own communities.

Diving deeper into the psychology, it would not be absurd to suggest that online followership may lead to toxic levels of self-conceit. In his blog “Muslimology,” Dawud Israel questions the febrile adulation of religious scholars. After Muslim followers heap piles of praise on their shuyukh after a khutba, Dawud wonders, “Who wouldn’t go on an ego trip?” It is no different in the social media world where Muslims engage in unrelenting flattery of their scholars’ posts and pictures. Are scholars immune to inordinate dosages of flattery? It may well be that none of us are. Promotion of the self is not a regrettable byproduct of social media, it is inherent to the institution itself! We seek validation and praise by publicizing our lives, careers, goals, interests, and talents. We all teeter on the brink of hubris. Should scholars be held to a different standard?

On a flight to San Francisco I ran into Shaykh Hamza Yusuf, arguably one of the most influential Muslim scholars in the West. In a classy black suit and round horn-rimmed glasses, he addressed the flight attendant with an air of gravitas. Resisting the pestilent urge to pull out my phone and Snapchat him, I asked for his thoughts on Muslim celebrity scholar culture. Yusuf had an overall pessimistic outlook on social media. “People tell me to get a Twitter,” he said, “but you know I won’t do it.” While skeptical of the intellectually nullifying reality of social media including the concept of blogging, Yusuf took a conciliatory tone. He conceded that at least Muslims were following religious scholars instead of frivolous famous personalities. “It’s human nature,” he admitted, “to follow who you love.”

It’s true. We love our Muslim scholars so much so that we jump at the first chance to follow their lives; and they indubitably mean well in their efforts to reach and relate to a tech-savvy generation. But we must question the psychological and sociological impact of this culture on our collective Muslim ethos. Out of this very human and sincere love, celebrity scholars and follower-fans must ask themselves these hard-hitting questions.